When I started reading the sonnets of Raymond Jacobs’s Beyond Rhymes, Beyond Reason, one of my first reactions was, “why would anyone ever try to write a sonnet today?”

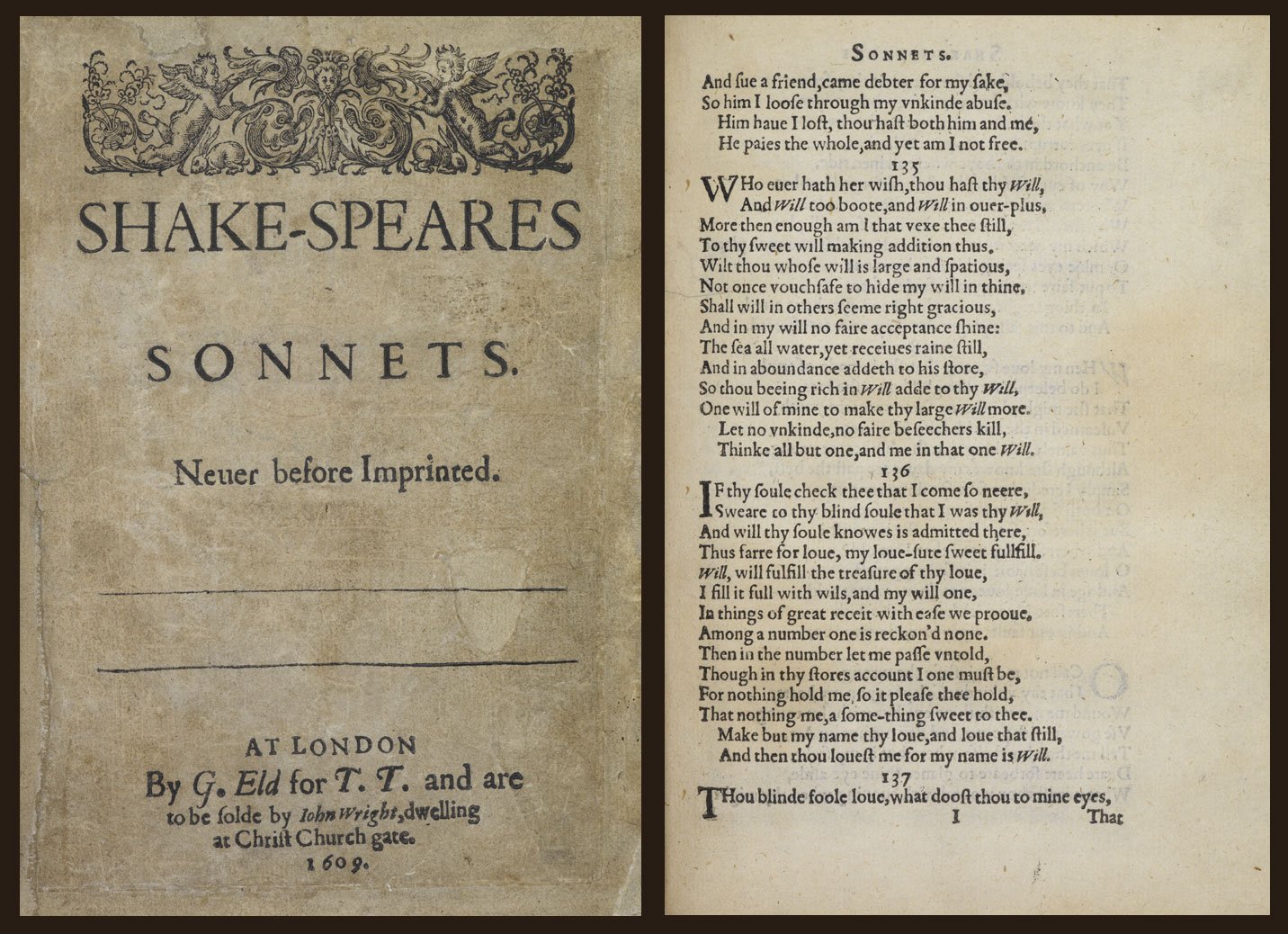

The sonnet form seems like a leftover from another world, a world that’s not our own.

Over the years, in two different professional careers, I’ve been lucky enough to have many chances to see the kinds of poetry being written and published now. Most of it—at least what I’ve encountered—isn’t like what you find between the covers of Beyond Rhymes, Beyond Reason.

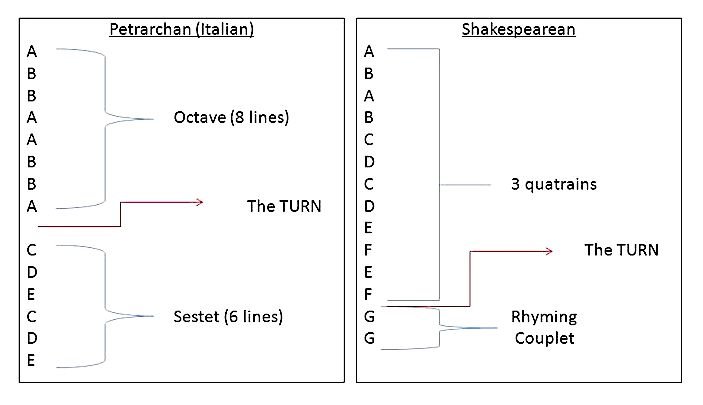

Today’s acclaimed poets (many of whom have retreated into academia in order to pay the bills) don’t really embrace the old-fashioned sonnet form (or, for that matter, any old-fashioned form), and they certainly don’t appreciate the way an end-rhyme can cause two lines to snap into place as snugly as a pair of Legos.

Most—to me anyways—have abandoned the classical poetic forms and the kinds of familiar rhythms that Jacobs uses so devotedly here. Instead, they draw their organization (and sense of order) from very personal, very private mythologies that readers have to struggle to decipher—not to mention the bewildering imagery that often makes as little sense as a Jackson Pollock painting.

Their defenders will tell you that contemporary poetry is supposed to reflect the world we live in, and if today’s poetry is fragmented and hard to understand, well, that’s because our world is.

Fair enough, I’d say, but who is this poetry for? Who’s the audience? If there isn’t one, what’s the point? That defense doesn’t make their work any more readable (or understandable).

Which is why Jacobs’s efforts in this volume are truly appreciated. As he will tell you, and as I learned when I first talked to him about his work several years ago, he is a firm disciple of familiar, anthologized poets who belong to the “old school” way of doing things—poets like Robert Frost and Percy Shelley who believed that the structure and framing of a poem is just as important as its contents, and that accessibility isn’t something to be ashamed about.

To bring that old world style into ours, and to avoid calling too much attention to it, Jacobs is very careful and restrained with his language here. His voice in these poems avoids too much of the embroidered, flowery language a courtier poet might have used four or five centuries ago.

What I especially appreciate is that he’s using rhyme and meter as a response to the disordered, Twittered, Tik-tokked world in which we live, and he uses it the way anyone does who chooses to wear a favorite sweater or coat—as something that’s familiar and comfortable, as a bit of reassurance, as a way to keep things in check.

***

Raymond Jacobs

Like the courtier poets of old, Jacobs does share a very familiar theme with them in Beyond Rhymes, Beyond Reason.

In fact, it’s that most ancient of themes, of romantic desire and unrequited love, that has fueled everyone from Sextus Propertius to Dante to Petrarch to Thomas Wyatt to Shakespeare to Derek and the Dominos (and everyone else in between).

When love isn’t returned or ends abruptly, it doesn’t have to be the end. It might be tempting to give in and let depression and loneliness take over, which Jacobs describes in “The Naked Truth”:

The nights I lay unwanted

Are when I feel most haunted

By the melancholy effect

Of human neglect

But another option is to take that sorrow and disappointment, as Jacobs does, and carefully explore it. In Beyond Rhymes, Beyond Reason, Jacobs captures both the pleasure and pain of falling in love, especially those difficult moments when there’s plenty of passion but, as he laments in “Checkmate,” it hasn’t been fulfilled yet:

How is it that I have the will

To love you as I do still

When the bonds of our affinity

Have yet to share in the divinity

Of intimacy

His language is warm and exuberant, sometimes faintly echoing (to my ear) the lyrics of a pop songwriter, which he does in “Because You Are”:

You are my one and only

Whenever I am lonely,

You are the touch that has come to fashion

The very fabric of my passion,

You are the pure reflection

Of my most intimate affection

Jacobs’s effort to pin down and examine his joy and pain attests to that challenge. He doesn’t hide the fact that writing this way is challenging; several times, in fact, he calls our attention to his struggle to wrestle his feelings into the proper meter and form. In “A Jester’s Waltz,” for example, he says:

It is for no just cause

That I dance without applause

Among those of you who are immune

To the melodic beat of a tune

That accompanies my every stride

Elsewhere, in “A Final Rendering,” he declares with a note of annoyance: “To be in search of the perfect verse/Can often be a nagging curse.”

Anyone who has ever tried capturing their feelings in a poem will surely understand—and probably agree with him.

***

Twenty years in the making, Beyond Rhymes, Beyond Reason is a candid and honest book. Jacobs doesn’t twist his circumstances in order to find a false silver lining. He merely accepts what he cannot change and transforms it into art.

Nothing is permanent, he concedes late in the book, not even love—not even a love that’s been given a chance. That realization comes to him during a quiet moment at the grave of the woman’s father. All of us pass away, he seems to suggest, and the only thing that’s left behind is a gravestone as a reminder of a life once lived. Or, in the case of a passion felt for another person, a poem. Or a book .

That’s the special consolation that Beyond Rhymes, Beyond Reason provides—that poetry can (and will) last long after our feelings and other things have gone away.

***

——(Adapted from the introduction to Beyond Rhymes, Beyond Reason. For more information about the book, contact the author via his LinkedIn account. He’d be happy to hear from you!)